Steam, Steel, and Infinite Minds

蒸汽、钢铁与无限的思维

Every era is shaped by its miracle material. Steel forged the Gilded Age. Semiconductors switched on the Digital Age. Now AI has arrived as infinite minds. If history teaches us anything, those who master the material define the era.

每个时代都由其神奇的材料塑造而成。钢铁铸就了镀金时代,半导体开启了数字时代,如今人工智能以其无限的智能面貌横空出世。历史告诉我们,掌握了某种材料的人,才能定义一个时代。

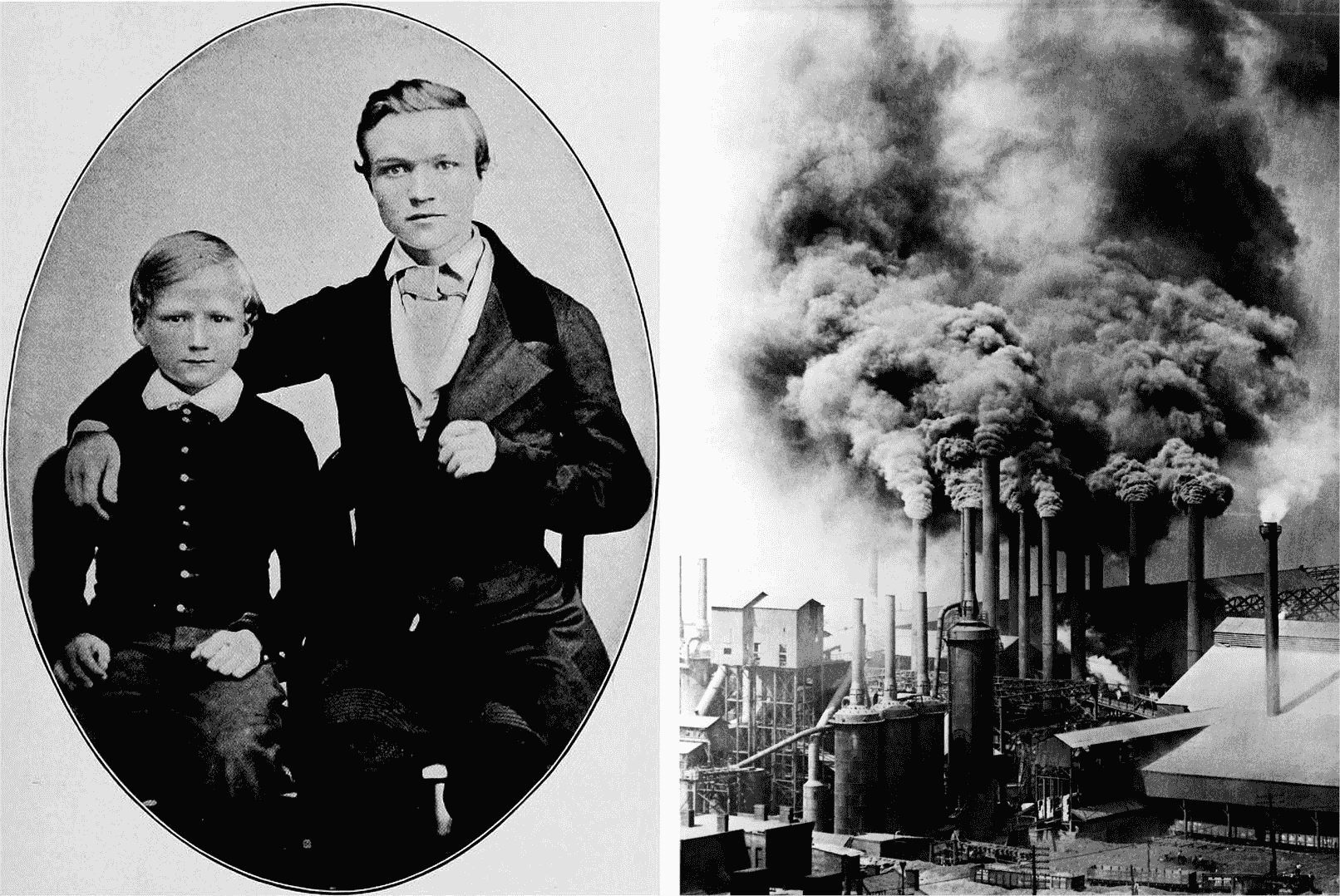

Left: teenage Andrew Carnegie and his younger brother.

左图:少年安德鲁·卡内基和他的弟弟。

Right: Pittsburg steel factories during the Glided Age.

右图:滑翔时代匹兹堡的钢铁厂。

In the 1850s, Andrew Carnegie ran through muddy Pittsburgh streets as a telegraph boy. Six in ten Americans were farmers. Within two generations, Carnegie and his peers forged the modern world. Horses gave way to railroads, candlelight to electricity, iron to steel.

19世纪50年代,安德鲁·卡内基曾是匹兹堡泥泞街道上的电报员。当时,十分之六的美国人是农民。仅仅两代人的时间,卡内基和他的同辈人就缔造了现代世界。马匹被铁路取代,烛光被电力取代,钢铁被钢铁取代。

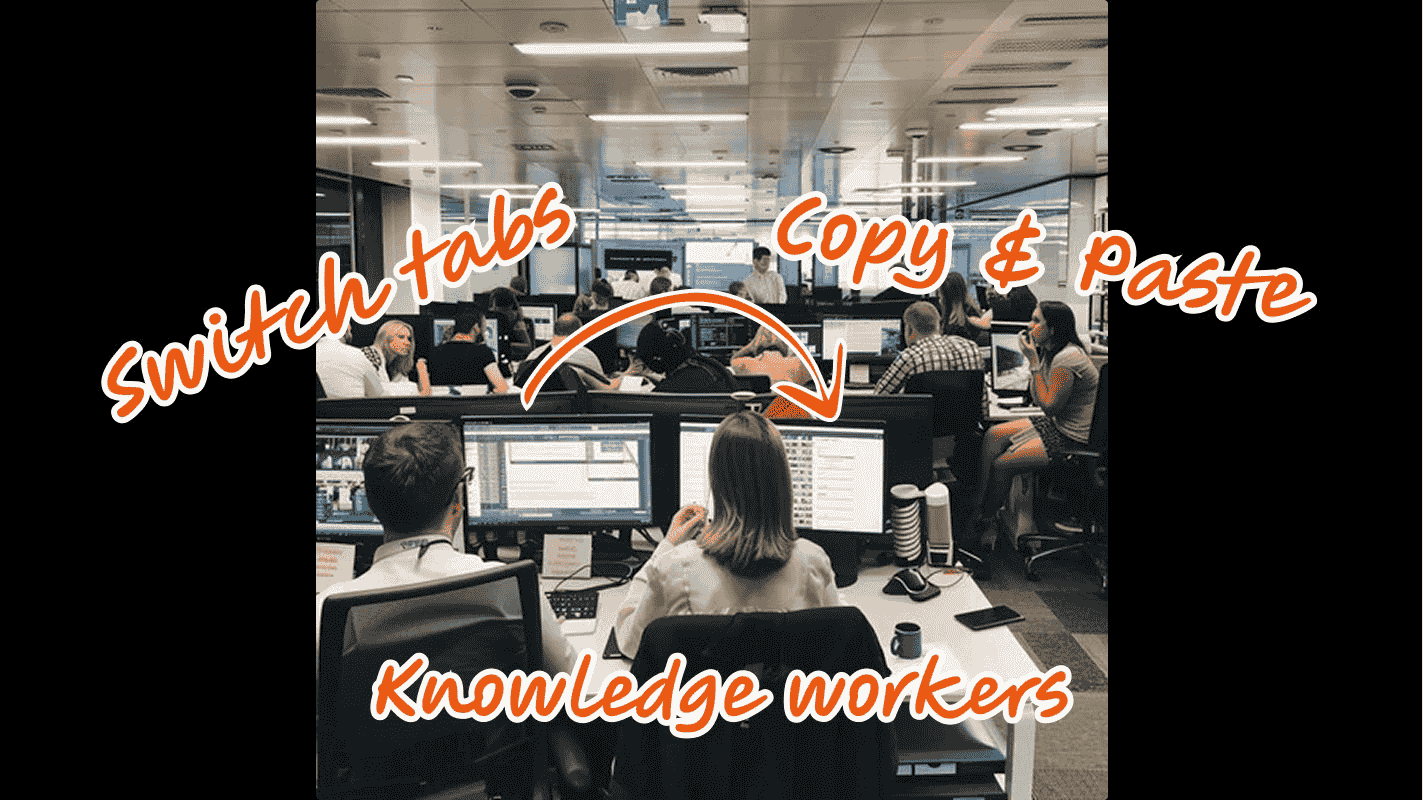

Since then, work shifted from factories to offices. Today I run a software company in San Francisco, building tools for millions of knowledge workers. In this industry town, everyone is talking about AGI, but most of the two billion desk workers have yet to feel it. What will knowledge work look like soon? What happens when the org chart absorbs minds that never sleep?

自那时起,工作重心从工厂转移到了办公室。如今,我在旧金山经营一家软件公司,为数百万知识工作者开发工具。在这个工业重镇,人人都谈论着通用人工智能(AGI),但 20 亿上班族中的大多数人却尚未感受到它的影响。知识型工作未来会是什么样子?当组织架构容纳了那些永不眠的头脑时,又会发生什么?

Early movies often looked like stage plays, with one camera focusedon the stage.

早期电影往往看起来像舞台剧,只有一个镜头对准舞台。

This future is often difficult to predict because it always disguises itself as the past. Early phone calls were concise like telegrams. Early movies looked like filmed plays. (This is what Marshall McLuhan called “driving to the future via the rearview window.”)

未来往往难以预测,因为它总是伪装成过去。早期的电话就像电报一样简洁。早期的电影看起来像是舞台剧的录像。( 这就是马歇尔·麦克卢汉所说的“透过后视镜驶向未来”。 )

The most popular form of Al today look like Google search of the pastTo quote Marshall

McLuhan: “we are always driving into the future via the rearview window

如今最流行的AI形式看起来很像过去的谷歌搜索。正如马歇尔·麦克卢汉所说:”我们总是透过后视

镜驶向未来。

Today, we see this as AI chatbots which mimic Google search boxes. We’re now deep in that uncomfortable transition phase which happens with every new technology shift.

如今,我们看到的就是模仿谷歌搜索框的人工智能聊天机器人。我们现在正深陷于每次新技术变革都会经历的那种令人不适的过渡阶段。

I don’t have all the answers on what comes next. But I like to play with a few historical metaphors to think about how AI can work at different scales, from individuals to organizations to whole economies.

我无法预知未来会发生什么。但我喜欢运用一些历史比喻来思考人工智能如何在不同层面上发挥作用,从个人到组织再到整个经济体。

Individuals: from bicycles to cars

个人:从自行车到汽车

The first glimpses can be found with the high priests of knowledge work: programmers.

我们最早能从知识工作的领军人物——程序员身上看到这种现象。

My co-founder Simon was what we call a 10× programmer, but he rarely writes code these days. Walk by his desk and you’ll see him orchestrating three or four AI coding agents at once, and they don’t just type faster, they think, which together makes him a 30-40× engineer. He queues tasks before lunch or bed, letting them work while he’s away. He’s become a manager of infinite minds.

我的联合创始人西蒙以前是我们所说的“十倍速程序员”,但他现在很少写代码了。你只要走到他的办公桌旁,就会看到他同时操控着三四个人工智能编码代理,它们不仅打字快,还会思考,这让他的效率达到了30到40倍。他会在午饭前或睡前安排好任务,让它们在他离开的时候继续工作。他现在就像一个管理着无数个智能体的管理者。

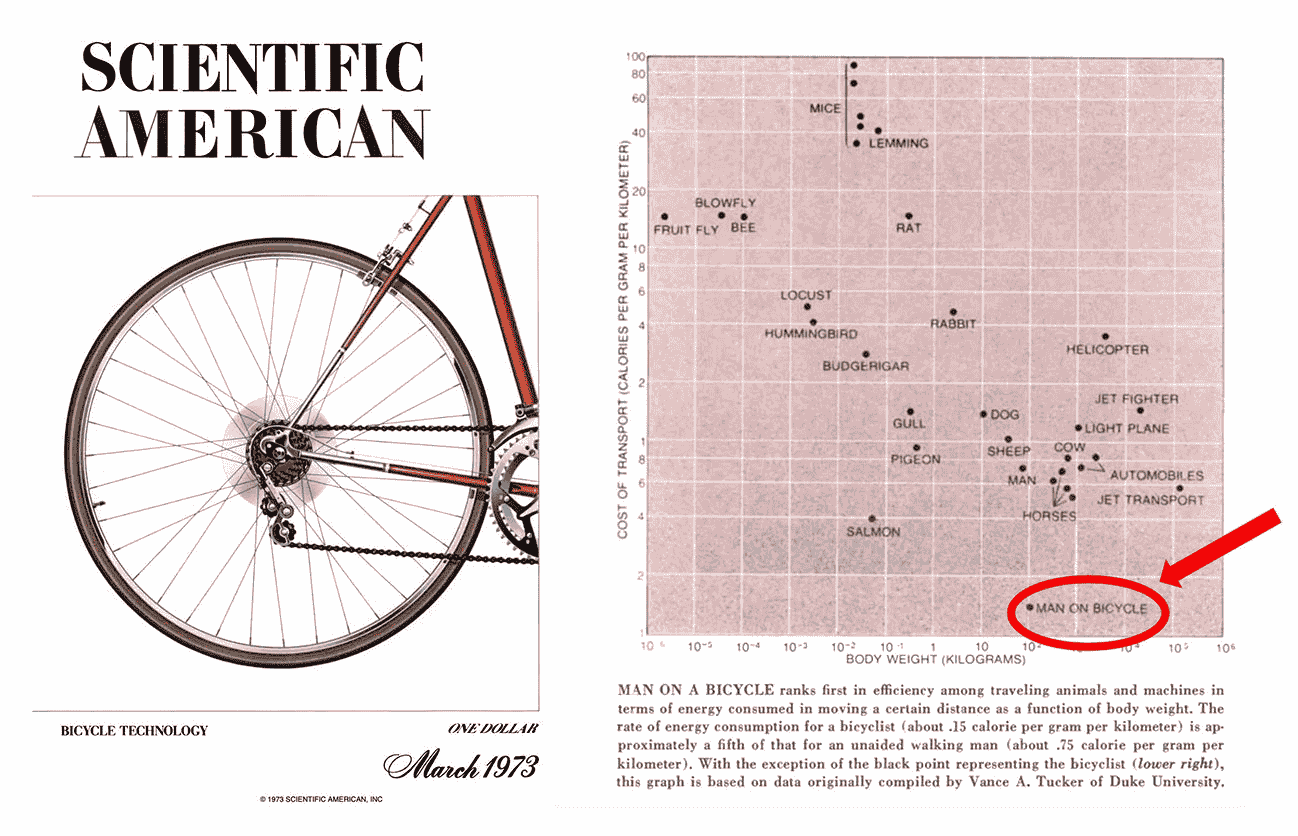

A 1970s Scientific American study on locomotion efficiencyinspired Steve Jobs’s famous

‘bicycle for the mind’ metaphor. Except we’ve been pedaling on theInformation Superhighway

for decades since.

20世纪70年代《科学美国人》杂志上一篇关于运动效率的研究启发了史蒂夫·乔布斯著名的”思维自

行车”比喻。只不过,几十年来,我们一直在信息高速公路上骑行。

In the 1980s, Steve Jobs called personal computers “bicycles for the mind.” A decade later, we paved the “information superhighway” that is the internet. But today, most knowledge work is still human-powered. It’s like we’ve been pedaling bicycles on the autobahn.

上世纪80年代,史蒂夫·乔布斯称个人电脑为“思维的自行车”。十年后,我们铺设了互联网这条“信息高速公路”。但如今,大多数知识型工作仍然依赖人力。这就像我们一直在高速公路上骑自行车一样。

With AI agents, someone like Simon has graduated from riding a bicycle to driving a car.

借助人工智能代理,像西蒙这样的人已经从骑自行车升级到了开车。

When will other types of knowledge workers get cars? Two problems must be solved.

其他类型的知识工作者何时才能拥有汽车?这需要解决两个问题。

Comparing with coding agent, why is it more difficult for Al to help with wledge work?

Because knowledge work is more fragmented and less verifiabble.

与编码代理相比,为什么人工智能更难协助处理知识型工作?因为知识型工作更加分散,且更难验

证。

First, context fragmentation. For coding, tools and context tend to live in one place: the IDE, the repo, the terminal. But general knowledge work is scattered across dozens of tools. Imagine an AI agent trying to draft a product brief: it needs to pull from Slack threads, a strategy doc, last quarter’s metrics in a dashboard, and institutional memory that lives only in someone’s head. Today, humans are the glue, stitching all that together with copy-paste and switching between browser tabs. Until that context is consolidated, agents will stay stuck in narrow use-cases.

首先是上下文碎片化。 对于编码而言,工具和上下文往往集中在一个地方:集成开发环境(IDE)、代码仓库、终端。但通用知识的工作却分散在几十个工具中。想象一下,一个人工智能代理要撰写一份产品简介:它需要从 Slack 聊天记录、战略文档、仪表盘上季度的指标数据以及只存在于某人脑海中的机构记忆中提取信息。如今,人类就像粘合剂,通过复制粘贴和切换浏览器标签页将所有这些信息拼接起来。除非上下文得到整合,否则代理将始终局限于狭窄的使用场景。

The second missing ingredient is verifiability. Code has a magical property: you can verify it with tests and errors. Model makers use this to train AI to get better at coding (e.g. reinforcement learning). But how do you verify if a project is managed well, or if a strategy memo is any good? We haven’t yet found ways to improve models for general knowledge work. So humans still need to be in the loop to supervise, guide, and show what good looks like.

第二个缺失的要素是可验证性。 代码具有一种神奇的特性:你可以通过测试和错误来验证它。模型构建者利用这一点来训练人工智能,使其更好地进行编码(例如强化学习)。但是,如何验证一个项目是否管理得当,或者一份战略备忘录是否有效呢?我们尚未找到改进通用知识模型的方法。因此,人类仍然需要参与其中,进行监督、指导,并展示什么是好的模型。

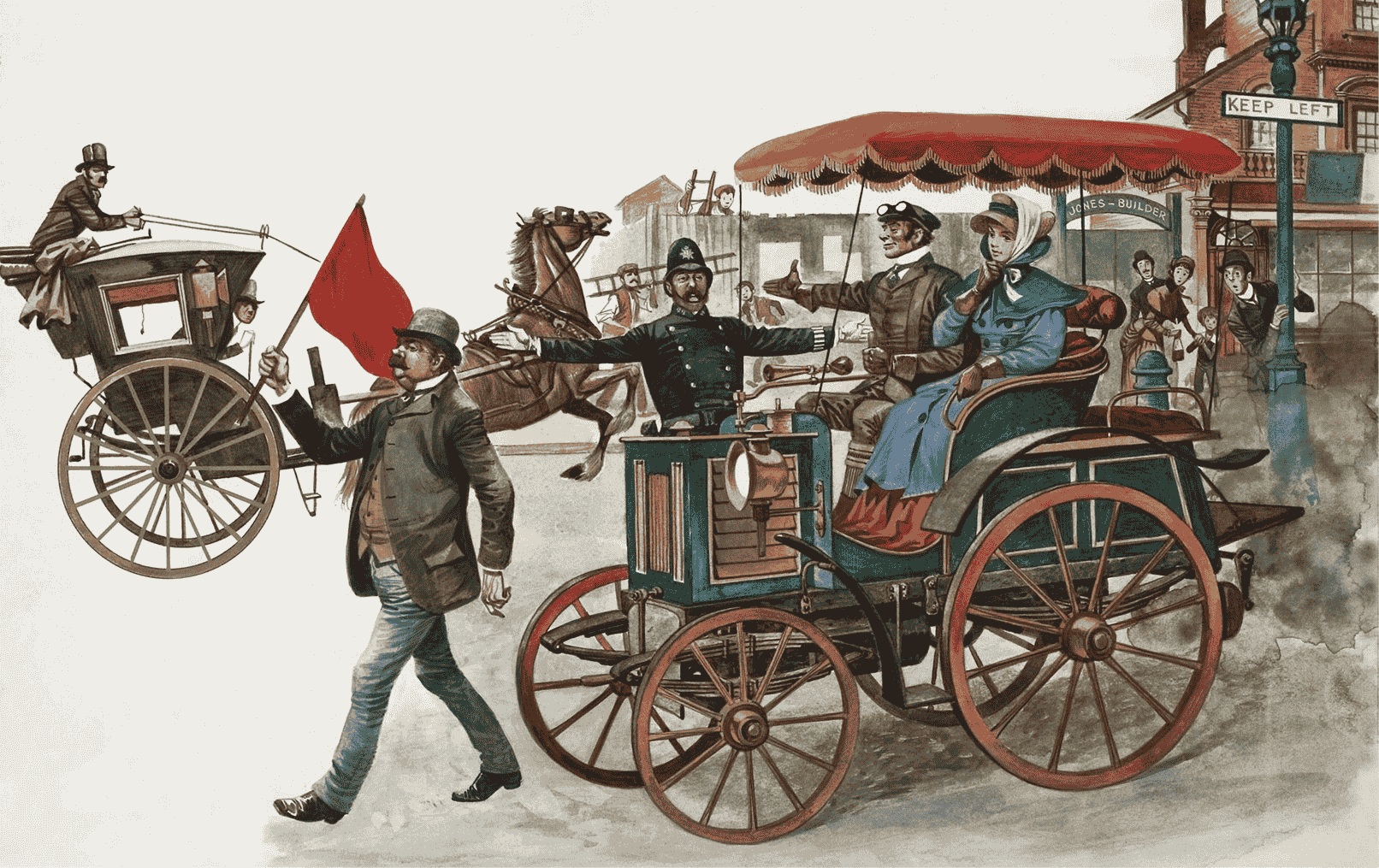

The Red Flag Act of 1865 required a flag bearer to walk ahead of the vehicle while it drove down

the street (repealed in 1896). An example of undesirable “human itn the loop.”

1865年的《红旗法案》要求在车辆行驶时,必须有一名旗手走在车前(该法案于1896年废除)。

这是一个令人不快的”人为干预”的例子。

Programming agents this year taught us that having a “human-in-the-loop” isn’t always desirable. It’s like having someone personally inspect every bolt on a factory line, or walk in front of a car to clear the road (see: the Red Flag Act of 1865). We want humans to supervise the loops from a leveraged point, not be in them. Once context is consolidated and work is verifiable, billions of workers will go from pedaling to driving, and then from driving to self-driving.

今年的编程智能体让我们明白,“人机协同”并非总是可取的。这就像让一个人亲自检查工厂生产线上的每一个螺栓,或者走到车前清理道路(参见1865年的《红旗法案》)。我们希望人类从旁观者的角度监督整个流程,而不是身处其中。一旦上下文信息整合完毕,工作成果可验证,数十亿劳动者将从骑车过渡到驾驶,最终从驾驶过渡到自动驾驶。

Organizations: steel and steam

组织:钢铁和蒸汽

Companies are a recent invention. They degrade as they scale and reach their limit.

公司是近代才出现的产物。随着规模扩大,它们会逐渐衰落,最终达到极限。

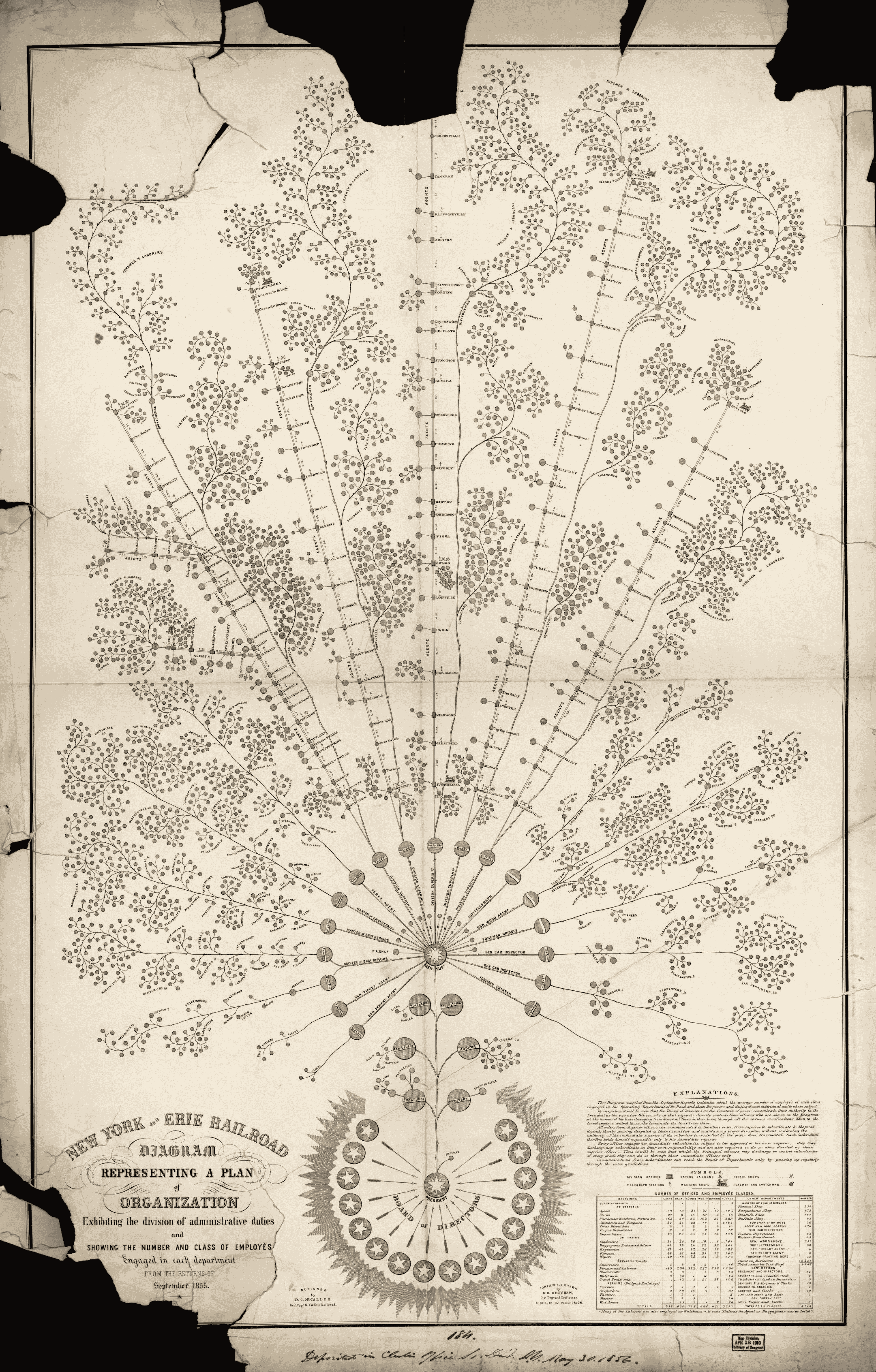

Organizational chart for the New York and Erie Railroad, 1855. The modercorporation and org

chart evolved with the railroad companies, which were the first enterprises that needed to

coordinate thousands of people across great distances.

1855年纽约和伊利铁路的组织结构图。现代公司和组织结构图随着铁路公司的发展而演变,铁路

公司是第一批需要协调数千人跨越遥远距离的企业。

A few hundred years ago, most companies were workshops of a dozen people. Now we have multinationals with hundreds of thousands. The communication infrastructure (human brains connected by meetings and messages) buckles under exponential load. We try to solve this with hierarchy, process, and documentation. But we’ve been solving an industrial-scale problem with human-scale tools, like building a skyscraper with wood.

几百年前,大多数公司都只是十几人的作坊。如今,跨国公司拥有数十万员工。沟通基础设施(人脑通过会议和信息连接起来)在指数级增长的负荷下不堪重负。我们试图通过层级结构、流程和文档来解决这个问题。但我们一直用人类规模的工具来解决工业规模的问题,就像用木头建造摩天大楼一样。

Two historical metaphors show how future organizations can look differently with new miracle materials.

两个历史隐喻表明,借助新型神奇材料,未来的组织可以呈现出不同的面貌。

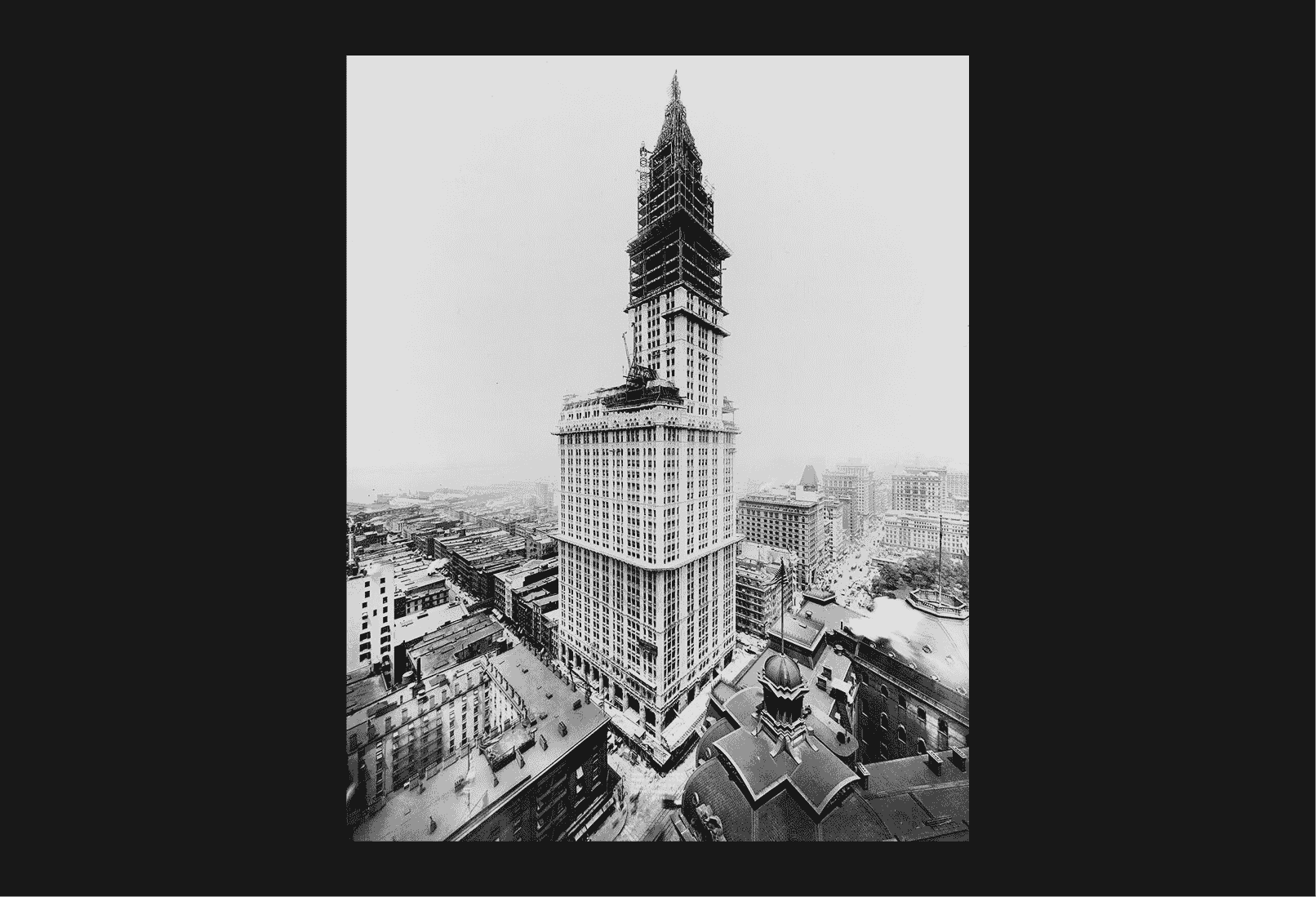

A wonder of steel: the Woolworth building was the tallest building inthe world upon

completion in NYC, 1913.

钢铁奇迹:伍尔沃斯大厦于1913年在纽约市竣工时,是当时世界上最高的建筑。

The first is steel. Before steel, buildings in the 19th century had a limit of six or seven floors. Iron was strong but brittle and heavy; add more floors, and the structure collapsed under its own weight. Steel changed everything. It’s strong yet malleable. Frames could be lighter, walls thinner, and suddenly buildings could rise dozens of stories. New kinds of buildings became possible.

首先是钢材。在钢材出现之前,19世纪的建筑最多只能建六七层。铁虽然坚固,但却易碎且笨重;增加楼层数,建筑就会因自身重量而坍塌。钢材的出现彻底改变了这一切。它既坚固又具有良好的延展性。框架可以做得更轻,墙体可以做得更薄,建筑物也因此可以高达数十层。新型建筑由此成为可能。

AI is steel for organizations. It has the potential to maintain context across workflows and surface decisions when needed without the noise. Human communication no longer has to be the load-bearing wall. The weekly two-hour alignment meeting becomes a five-minute async review. The executive decision that required three levels of approval might soon happen in minutes. Companies can scale, truly scale, without the degradation we’ve accepted as inevitable.

人工智能是企业的钢铁。 它能够贯穿整个工作流程,并在需要时提供清晰的决策依据,避免信息干扰。人际沟通不再是重担。每周两小时的协调会议可以简化为五分钟的异步评审。过去需要三级审批的决策,可能很快就能在几分钟内完成。企业可以真正实现规模化增长,而无需承受我们过去习以为常的性能下降。

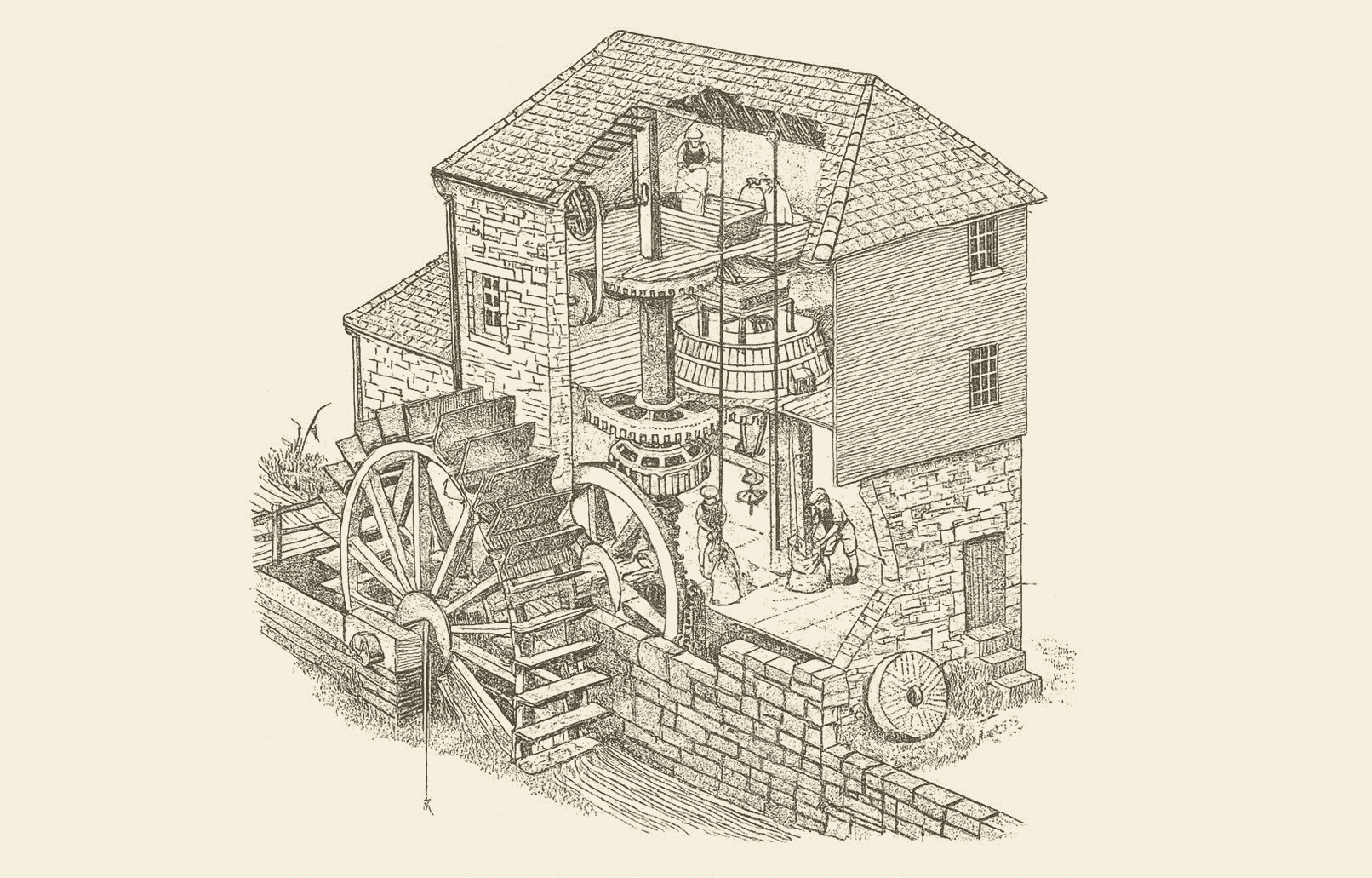

A mill with a water wheel to power its operations. Water was powerful but reliable and

restricted mills to a few locations and seasonality.

以水车为动力运转的磨坊。水力虽然强大,但供应不稳定,因此磨坊的选址和建造都受到季节的限

制。

The second story is about the steam engine. At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, early textile factories sat next to rivers and streams and were powered by waterwheels. When the steam engine arrived, factory owners initially swapped waterwheels for steam engines and kept everything else the same. Productivity gains were modest.

第二个故事是关于蒸汽机的。工业革命初期,早期的纺织厂都建在河流溪涧旁,依靠水车驱动。蒸汽机出现后,工厂主最初只是用蒸汽机取代了水车,其他设备则保持不变。生产效率的提升并不显著。

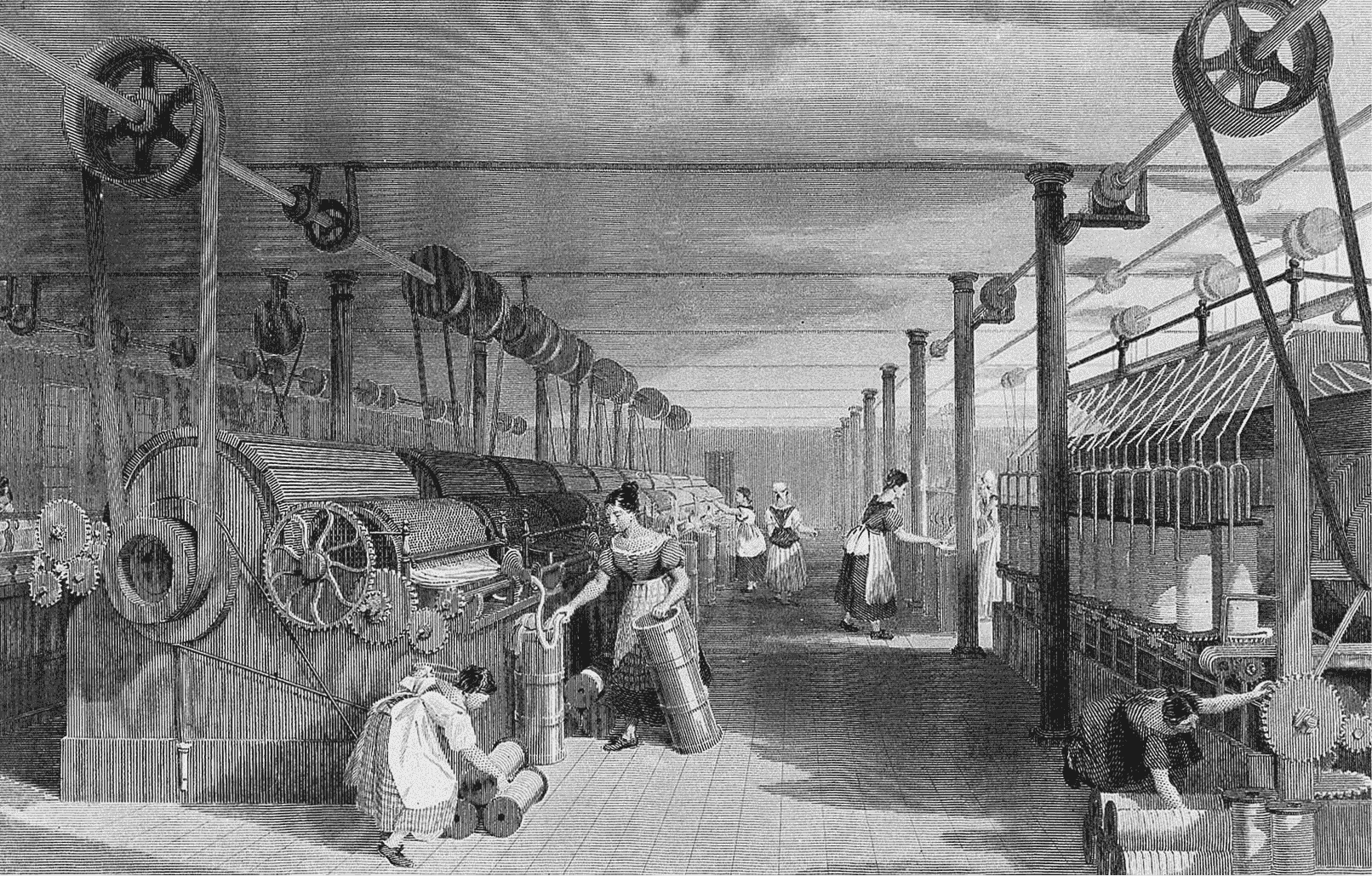

The real breakthrough came when factory owners realized they could decouple from water entirely. They built larger mills closer to workers, ports, and raw materials. And they redesigned their factories around steam engines (Later, when electricity came online, owners further decentralized away from a central power shaft and placed smaller engines around the factory for different machines.) Productivity exploded, and the Second Industrial Revolution really took off.

真正的突破出现在工厂主意识到他们可以完全摆脱对水的依赖之后。他们建造了更大的工厂,靠近工人、港口和原材料产地。他们围绕蒸汽机重新设计了工厂。(后来,随着电力普及,工厂主进一步分散了动力,不再依赖中央动力轴,而是在工厂各处安装小型发动机,为不同的机器提供动力。)生产力突飞猛进,第二次工业革命真正开始了。

This 1835 engraving by Thomas Allom depicts a textile factory in Lancashhire, UK. It was

powered by steam engines.

托马斯·阿洛姆于1835年创作的这幅版画描绘了英国兰开夏郡的一家级织厂。该厂由蒸汽机驱动。

We’re still in the “swap out the waterwheel” phase. AI chatbots bolted onto existing tools. We haven’t reimagined what organizations look like when the old constraints dissolve and your company can run on infinite minds that work while you sleep.

我们仍处于“替换水车”阶段, 人工智能聊天机器人只是简单地附加到现有工具上。我们还没有重新构想,当旧的限制消失,公司可以依靠无限的智能系统在你睡觉时运转时,组织会是什么样子。

At my company Notion, we have been experimenting. Alongside our 1,000 employees, more than 700 agents now handle repetitive work. They take meeting notes and answer questions to synthesize tribal knowledge. They field IT requests and log customer feedback. They help new hires onboard with employee benefits. They write weekly status reports so people don’t have to copy-paste. And this is just baby steps. The real gains are limited only by our imagination and inertia.

在我的公司 Notion,我们一直在进行一些尝试。除了我们 1000 名员工之外,现在还有 700 多名客服人员负责处理重复性工作。他们负责会议记录、解答问题,以整合内部知识。他们处理 IT 请求、记录客户反馈。他们帮助新员工了解员工福利。他们撰写每周状态报告,这样大家就不用复制粘贴了。而这仅仅是迈出了一小步。真正的进步只受限于我们的想象力和惯性。

Economies: from Florence to megacities

经济体:从佛罗伦萨到特大城市

Steel and steam didn’t just change buildings and factories. They changed cities.

钢铁和蒸汽不仅改变了建筑物和工厂,它们也改变了城市。

Until a few hundred years ago, cities were human-scaled. You could walk across Florence in forty minutes. The rhythm of life was set by how far a person could walk, how loud a voice could carry.

几百年前,城市的规模还很适宜人类居住。在佛罗伦萨,步行只需四十分钟就能横穿整个城市。当时的生活节奏取决于一个人能走多远,声音能传多远。

Then steel frames made skyscrapers possible. Steam engines powered railways that connected city centers to hinterlands. Elevators, subways, highways followed. Cities exploded in scale and density. Tokyo. Chongqing. Dallas.

随后,钢结构框架使摩天大楼成为可能。蒸汽机驱动的铁路连接了城市中心和内陆地区。电梯、地铁和高速公路也相继出现。城市的规模和密度呈爆炸式增长。东京、重庆、达拉斯。

These aren’t just bigger versions of Florence. They’re different ways of living. Megacities are disorienting, anonymous, harder to navigate. That illegibility is the price of scale. But they also offer more opportunity, more freedom. More people doing more things in more combinations than a human-scaled Renaissance city could support.

这些城市不仅仅是佛罗伦萨的放大版,它们代表着不同的生活方式。特大城市令人迷失方向,充满陌生感,难以辨认方向。这种难以辨认的特点正是规模带来的代价。但它们也提供了更多的机遇和自由。更多的人从事着更多的工作,组合方式也更加多样化,这是文艺复兴时期规模适中的城市所无法比拟的。

I think the knowledge economy is about to undergo the same transformation.

我认为知识经济也将经历同样的变革。

Today, knowledge work represents nearly half of America’s GDP. Most of it still operates at human scale: teams of dozens, workflows paced by meetings and email, organizations that buckle past a few hundred people. We’ve built Florences with stone and wood.

如今,知识型工作几乎占美国 GDP 的一半。但其中大部分仍然以人为本:几十人的团队,以会议和电子邮件为主导的工作流程,以及员工人数超过几百人就难以维系的组织。我们用石头和木头建造了佛罗伦萨。

When AI agents come online at scale, we’ll be building Tokyos. Organizations that span thousands of agents and humans. Workflows that run continuously, across time zones, without waiting for someone to wake up. Decisions synthesized with just the right amount of human in the loop.

当人工智能代理大规模上线时,我们将构建出类似东京的组织。这些组织将由成千上万的代理和人员组成。工作流程将跨越时区持续运行,无需等待任何人起床。决策的制定将结合恰到好处的人工干预。

It will feel different. Faster, more leveraged, but also more disorienting at first. The rhythms of the weekly meeting, the quarterly planning cycle, and the annual review may stop making sense. New rhythms emerge. We lose some legibility. We gain scale and speed.

感觉会不一样。速度更快,效率更高,但起初也会更让人摸不着头脑。每周例会、季度计划和年度回顾的节奏可能会变得不再适用。新的节奏会涌现。我们会失去一些清晰度。但我们获得了规模和速度。

Beyond the waterwheels

水车之外

Every miracle material required people to stop seeing the world via the rearview mirror and start imagining the new one. Carnegie looked at steel and saw city skylines. Lancashire mill owners looked at steam engines and saw factory floors free from rivers.

每一种神奇材料的出现,都要求人们停止用后视镜看待世界,开始想象新的世界。卡内基看到钢铁,看到的是城市的天际线。兰开夏郡的工厂主们看到蒸汽机,看到的是没有河流的工厂车间。

We are still in the waterwheel phase of AI, bolting chatbots onto workflows designed for humans. We need to stop asking AI to be merely our copilots. We need to imagine what knowledge work could look like when human organizations are reinforced with steel, when busywork is delegated to minds that never sleep.

我们仍处于人工智能发展的初期阶段,将聊天机器人生硬地套用到为人类设计的工作流程中。我们不能再仅仅要求人工智能充当我们的副驾驶。我们需要想象,当人类组织像钢铁般坚固,当繁琐的工作被委派给永不眠的头脑时,知识型工作将会是什么样子。

Steam. Steel. Infinite minds. The next skyline is there, waiting for us to build it.

蒸汽,钢铁,无限的创意。下一个天际线就在那里,等待我们去创造。